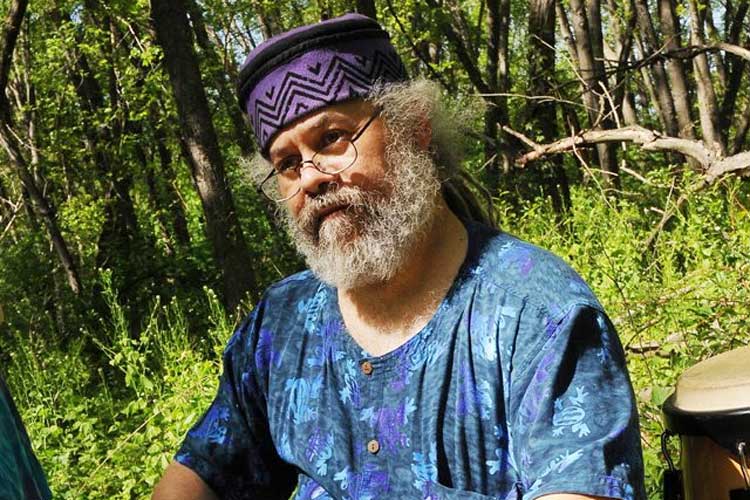

Jimi Two Feathers Interview

by Heather Bois

March 1997

I guess my first question should be about how you got involved in drumming.

I got started when I was your age, actually a little bit younger, and they used to have concerts on Sunday afternoons by the monument, and on the far side of the Cambridge common there were people playing congas. After the concerts were over, and I'd get bored or something, and eventually end up at the drummers.

There were some dancers there, and a flute player, and a bunch of drummers. They would drum until dark on Sundays. That was my first contact with the drum and its energy. I guess that made a profound change in me, because I am one of the pioneers from Cambridge. So we took the drummers and the dancers and decided, let's go inside, let's find a place to drum inside. That's how Dance Free got started, and out of that grew Dance New England, and now it's a movement that's all over the world.

Music and dance are one for me; music, dancing and singing, they're the same thing. You hear some people call themselves "drummers", some people call themselves "dancers", they're specialized. But, in some cultures in Africa, they'll have one word for all of these things. They'll never do one part or the other. It has to do with making choices. For many years I was a dancer. I always wanted to drum, and dancing is really hard on your body. My body gave out and my knees gave out, and that's when I started to drum. Around that time, I met Morwen and we started Earth Drum Council. The whole concept behind that was to create a safe place for people to go, kind of like what I had been doing with Dance Free, creating a safe place that was a smoke-free, alcohol-free space for people to drum.

Ultimately, I'm not a traditionalist . However, I believe that dancing and drumming around a fire is the original nightclub. I try to emulate that essence and that spirit of the tribal ways. The fire, drummers and dancers create a spirit of which there is no substitute. I've been doing this for twenty-nine years and I haven't had enough, I'm not tired and I'm not bored of it. Every time is a new experience for me.

I constantly see new people being pulled into it. That's really where the magic of it is for me. I've spent a lot of my time, especially the last eight years, creating spaces for people to dance and drum in a safe way. We've taken the workshops out on the road, done a lot of festivals. There seem to be many people who want to be around the drum, but don't know what to do with it. We try to get people to it.

Instead of having a jam become a complete mess of a lot of noise, there are subtle ways of keeping control. You want to have a lot of voices, but at the same time keep control, so there's space for them all to be heard. It's a very skillful art. I'm not a master drummer, even though I have been playing for a long time. What I am is a facilitator. I'm not looking at just my drum, I'm looking at the whole circle. If I was the master drummer, I'd be too busy being the master drummer, concentrating on what I'm playing to be watching and helping; I wouldn't be able to be flexible, to weave in and out.

Did you ever play the role of the master drummer?

No, not really. I've been the lead drummer in some performances, or the lead force in the energy around the fire. But, I'm not a master and I don't call myself a master. I'm an eternal beginner. And also, I think that's what helps keep the atmosphere of safety for the beginner. So that way, I don't appear to be on a different level than the beginners. I'm trying to remember all of the obstacles that I had to overcome when I was a beginner. It keeps me fresh.

So what do you mean by a safe environment?

OK, well there's a lot more to drumming than people understand or think. My perspective of it, because I am also African American, is that Baba Olatunji brought the drum here in the 50s. And he is a teacher. And he is a master. And he wanted to teach. At first he took the drum to the natural places that he would: to the black people. The people then, they were trying to create an identity, and get out of the inferior vein that the white people had given people of color. So, one of the results of that was that they said, "Wait, what do you mean, man? We don't dance around barefoot. We don't wear grass skirts. We don't play drums. We're modern American black people. We wear a suit and tie. We go to work, we've got a high-paying job. Just like the next white guy." So, when Olatunji went to the black community and said he wanted to teach them this ancient primitive art from their background, people laughed. A lot of black people do not know where they came from. That whole Roots thing is an exception to the rule. Most people, because of the concept of slavery, which was about taking people and removing them from their culture and losing their identity because of splitting up their families, have no idea where they came from. My family has no idea which part of Africa our heritage is from.

So, anyway, when Olatunji came here and wanted to teach the black people, they said, "No way, get away from me." He had to teach somebody. So he started teaching white people. After many years, you have a student, and regardless of what color he is, you've been teaching him for many years, that student had better know something, or what does that say of you as a teacher? You know, so now the issue is, who has the right to drum, and to teach drums? Can you be a teacher? Can you be a master? You're white. You're not from Africa. Well, most of these people aren't from Africa. Whether they're white or not.

Creating a safe space also includes the fact that when the recent wave of African drummers first came here, they wouldn't teach women. This is because in most of those cultures, the women danced and the men drummed. How dare you? You want to learn drumming? No way. Or even if they got someone to teach women, the men would push them out with their "macho energy" and would push the women out, or the teacher wouldn't give you a solo, or a chance, or pay any attention to you.

Our concept was that everyone has the right to touch the drum. There are cultures where only the women drum, and the men dance. And there are cultures where one does this and one does the other. What we wanted to do was break these barriers, we wanted to open it up. We saw that in the future, there was going to be this huge influx of people coming and testing the energy of the drum. There's something about it, some energy that it raises. Now, the question is, what to do with that energy? If you're trained at all, you can do a lot with it. Some people are just drawn to it, and they don't know what to do with it. So of course you have to train these people, and the way to train somebody is to tell them, "You can do this. It's OK."

So, we create a safe space by only hiring teachers that follow this philosophy. These teachers can't be reactionary to having women in the class, and can't be derogatory to the women. Now, it's gone the other way around to the point where we've got teachers who are very limited, as our community is strong, in that they're teaching teachers. Everybody is a teacher. And also, we don't want to put people up here (raises his hand high above the table). Even if they are a master. Still, you want to respect the teacher for the knowledge that they have. But Einstein, even he couldn't spell. He was a master in his own art, but he was a weak and deficient person in a lot of other ways. And a lot of times people are out of balance. They're really good at one thing, but they're missing a lot of other things, because they spend so much time on that one thing. They don't really become well-rounded.

Basically, that's the tip of the iceberg in what creating safety is. Part of what safety is now is letting the white people grow. Because there are a lot of black people who had turned their back on the whole African thing. But now, they look at it like, "Hey man, there they go again. Now they're ripping our culture off. They're ripping our rhythms and traditions off." Well, you know something? Those are the same guys who didn't want to learn how to drum. If it wasn't for some of the white people today, those rhythms would have been lost.

So you basically feel that everyone should

be able to drum?

Yes. Everybody. No matter where they're from. I'm not saying that people shouldn't seek out and research their own culture and heritage. My Indian side of me says that the madness of the white man is that when they came over from Europe, they left the bones of their ancestors in graves far away. As soon as they did that, they became people without a land--people without a country. I think that a lot of the people of European descent need to go back and explore their heritage, and become proud of who they are. Not to be proud of some Indian name, or some African name, but of who they are. But that's a double-edged sword, because when you create that pride, you create nationalism. And you know what happens when you create nationalism. We have wars. We have this group over here, looking at that group over there and says, "We're gonna wipe this group out!" So, there has to be a balance. You have to have enough pride in yourself to know who you are, but at the same time, you can't think that you're better than anyone else and that you're going to wipe them out. That's the tough part.

Do you think that your African-American and your Native American background had something to do with your interest in drumming?

No. I believe that everyone has a heartbeat. You walk. You put one foot in front of the other. Everyone has rhythm. Every culture has rhythm. Every culture has drumming. Even the European cultures, before Christianity, had drumming. So I don't believe that something involving my blood had something to do with that. I don't believe that. I do think that maybe it brought me closer to the drum more easily, because it was a part of my culture, and in exploring my heritage I found these things. But I didn't grow up on a reservation. I grew up down the street from here. I went to schools in Cambridge. But no, I don't feel special because of my heritage. I believe that everybody has it in them.

So, while you were growing up, drumming wasn't really a part of your family life?

No, I didn't know that I had any Native American blood in me until I was in college.

But some of your family is involved in drumming.

My immediate family. My wife and I, and our little son. But my 15-year-old, he's not interested, at least not at this time. But I kind of expect that. The old pendulum goes back and forth. Whatever I am, he's kind of counter to that. Eventually, he'll see the whole picture. There's an old saying, that a young son looks up and his father and says, "I want to be just like him," and around the teenage years he says, "I don't ever want to be like him." But then the child grows up and becomes wise and says, "Wow. I am just like him."

Now, it says in your biography on the Earth Drum Council homepage, and I'm quoting this, that you've been "exploring the connections between drumming, magic and community for many years." In all of these explorations, what are the connections that you've found?

Well, drumming, in raising energy, creates a space that creates a bond between people. When people come back to that space, over a period of time, they feel a sense of community. And it's natural evolution of human emotions, that needing to feel connected. Especially in our culture, the way it is today, where tribalism is an ingredient that's missing, which people so sorely want. I think that's why the commune came out in the 60s, people were trying to feel connected.

Now we all know that just because someone is inactively related to you, doesn't mean you're connected to them. You don't have to be connected to them. You can create your family, or your tribe, with people who you know will stick with you until the end. Nowadays, people try to find people who they have more in common with, so they have less to work out. So, people who are drawn to drumming, I think, find a lot of things inside of them which are similar.

Not everybody is drawn to it. Some aren't. However, I've found that there's very little in the middle. People are either attracted to it, or they repel from it. But the people who are attracted to it, have a lot of similar things in common, which they find if they give themselves time to explore. And these are people from all walks of life, with all different cultural, social, and economic backgrounds.

So, when they come together in a circle, in a drum and dance, all those things that separate them, even their culture and their race, seem to drop off and fall back. Just your primal essence comes out. Once you strip all of those things down through the rhythms, through the progression and transformance from one world and into another, in getting through to that center, that energy, that fire, you leave things at the gateway. You break down, and you find that what's left is the same for everybody. Whatever their reasons for getting there, you're the same. They experience that oneness together, and then they come out. That's why at Drum and Dance Saturday we have people hold hands together and touch the ground at the end of the night. If people just left, they'd drive off into a wall, because they open themselves up to all of this, and then they have to bottle it all back up inside again, so they can go out there (gesturing to indicate "the real world"). They remember that, and that's why they come back. For some of us, that's like our therapy. It's almost like, "Wow. I need a hit." It's like a drug. It's also like tearing yourself down, in the process of opening yourself up to this. That's one of the many ways that people keep themselves sane. Some people go to a shrink, sit on a couch. It works for some people.

So, do you think that you've created a family in this drumming community?

Well, yes and no. The true test of family for me is when things are really hard, to see where they're at. Sometimes it's been hard. But it's a test, and we've been through it. After that test, I think we're stronger than we were, and the next time something like that happens it will be a little bit easier to go through it. Even after a hard time, we still talk with each other and work with each other and move on.

I do think that within our community there is a core that drives it, a core of twenty or so people. And because of this strong connection, people are drawn to it. They want to know how to become a part of it. So, we say, "Just be here. Take the responsibility and do it." And if they come, over and over again, people will look at them and just say, "You're a part of the circle, just like we are." There's no membership that you buy, you just start showing up. If you see what needs to be done, you take care of it. And that's the natural gateway. People are self-selecting. Most of them don't know that. But if you want to be there, there's nobody who's going to stop you, except you.

There's a lot of people who work really hard to get here, and then once they're here, they look around and say, "Well, I'm here now. What's up?" Some people want to be a part of it so badly, and once they get to the center, they don't realize they're in the center, because there's nothing there but pure energy. It's the journey on the way. The bus ride. I could give you a bus ride to California, but once you get to California, you say, `"Now that I'm in California, what do I do?" Because it wasn't really going to California. It was what happened on the way, the adventure on the way there that is really what it's about. It's the ride, it's not the final destination.

So do you feel that some people get involved in drumming just to be a part of it?

Sure, a lot of them do, but they never really last. See, that's the wonderful thing about it. You can't fake it. You can either drum, or you can't drum. And I don't mean how good you are. I mean here (places his hand over his heart). There's the weeding out process. Some people can fake it for a little while, but even those who can drum can't fake it.

What do you consider "faking?"

Learning all the rhythms so you can be cool, going out there and getting the biggest and the loudest drum, and being in front, always knowing the rhythm, and always having something to say, never knowing when to stop playing. For me, that's the easiest part, what's hard is fitting into the circle, knowing what piece you play, what note you're on. Some people get diarrhea of the drum, they just play every note every time, they just never know when to stop playing.

I wanted to talk a little bit about teaching.

Do you teach at all?

I teach beginners and more facilitation skills, than I do a rhythm or a technique. Basically, how to put your hands on the drum, I can do that. I think that teaching itself is an art. The best teachers are not generally the best performers. You may be a master, but that doesn't mean necessarily that you have the skills to teach. Teaching is an innate ability, I believe. You can make a teacher out of anybody, but there are some people that just go with it very easily and that's their special skill and their talent. Those people aren't usually the best drummers or the best dancers. They're somewhere in the middle. They've got the technique, they understand the history. They have a way about them that makes it acceptable to people to learn from them.

My skill is in facilitation. My desire to teach is around other people's facilitation tools, so that I'm not the only one watching the whole picture. Just in case that I'm not there, the group can still meet, and they don't get lost. And of course, I try to teach by example, which is the hardest way to teach. That's about it for me with teaching.

When you do teach beginners, what do you want them to get out of drumming?

Mostly to feel relaxed, and to stop thinking, just let it go.

Now, what do you see as the future of drumming?

More people drumming, and what that means is more people becoming connected with the energy. So that it's easier for people to communicate, and it becomes much more of a household condition. I believe that it will become more accepted by the mass culture at large. It will be interesting to see in particular how the commercial culture will accept it, and what it will do with it. Ultimately, that drumming and dancing around the fire, that primal scene, they'll never be able to control that. If you try to record it or videotape it, it's not the same, people have been doing that, it's just not the same. You can't mess with it. You can't experience that unless you are a part of it.

So do you believe that the drum

is going to be commercialized?

Yes, it already is.

But more so, in the future?

No. No more than the attempts that have already been made to do so. I have no fears that it will be polluted, or lose its meaning, no more than it already has been. It's getting stronger than it has been, maybe over the past few years, but it never went away. I have no fears, and I believe that I have a responsibility in the future about where it goes, by what I do, and how I teach, who I work with and network with.